October 11, 2016

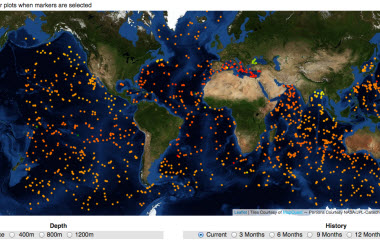

The COP17 (Conference of the Parties to CITES) is taking place now in Johannesburg, South Africa. CITES is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, a treaty drawn up in 1973 to ensure that the international trade of plants and animals does not threaten their survival. In short, it is a powerful tool to limit illegal trade of wildlife as it commits governments to shut down the market for wilfide products.  That means entry points like ports, harbors and airports have policies and procedures in place to disallow and prevent the import of species listed under the CITES agreement. The ultimate goal being to reduce the supply and demand of these endangered species as it becomes more and more difficult to procure endangered species.

That means entry points like ports, harbors and airports have policies and procedures in place to disallow and prevent the import of species listed under the CITES agreement. The ultimate goal being to reduce the supply and demand of these endangered species as it becomes more and more difficult to procure endangered species.

At this year’s COP17 meeting, sharks and rays are a hot topic. Silky sharks, thresher sharks, and mobula rays are being voted on for inclusion on Appendix II. "Appendix II includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival." That means that given the current rate of extraction, these species could quickly go from being reasonably abundant, to endangered very quickly. This is especially true for the two shark species that regularly fall victim to longline fishing gear and are either discarded as "bycatch" or their fins removed and smuggled into Asian ports for the shark fin soup trade. If you want to educate yourself more on the matter, check out the CITES brief that explains all the data and findings here.

Unfortunately, it is a lot more difficult to get sharks and rays listed on the CITES treaty than elephants, rhinoceros, or panda bears, because of their lack of visibility. Relatively speaking, there are far fewer people that have seen a shark, than an elephant, and the same goes for our government officials who make our laws and policies. Just a thought: Maybe it’s time for a Kickstarter campaign to get all the government officials in the world dive certified! This will give them all the opportunity to really see and experience the amazing marine life we’re asking them to protect. Who knows? It might be money well spent!

Unfortunately, it is a lot more difficult to get sharks and rays listed on the CITES treaty than elephants, rhinoceros, or panda bears, because of their lack of visibility. Relatively speaking, there are far fewer people that have seen a shark, than an elephant, and the same goes for our government officials who make our laws and policies. Just a thought: Maybe it’s time for a Kickstarter campaign to get all the government officials in the world dive certified! This will give them all the opportunity to really see and experience the amazing marine life we’re asking them to protect. Who knows? It might be money well spent!

Fingers crossed for the decisions made over the next couple of days at the COP17 and we hope that the sharks and rays proposed are added to the list. But that’s only half the battle. After that, it’s making sure all of the signatories for CITES follow through. Nonetheless, every step forward is a positive step towards the conservation and longevity of our marine life.

On October 4, 2016 the CITES Parties officially listed devil rays, thresher sharks, and the silky shark under Appendix II, which implies international trade restrictions to ensure all exports are sustainable and legal. The listing was supported by more than two-thirds of the voting parties.

Progress.